Music Theory

Mixolydian mode: famous examples in classical and pop music

The Cylix of Apollo with the Lyre

Musical Mode: Mixolydian Mode

In the 17th century, the major and minor scales became the basis for almost all classical music compositions. This evolutionary process is explained by the functional advantage of these seven-note scales over others since both the major and minor work with all three harmonic functions, namely tonic, dominant, and subdominant. Various interactions between these musical functions create tension and organically resolve it, causing a harmonic pulsation and determining the emotional spectrum.

In addition to major and minor, there are five more diatonic scales, including Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian, known from ancient Greece, though in modern musical theory they have other meanings. These so-called modal scales are used by classical composers to tie music to a specific area or to reflect the identity of folk culture. In the 20th century, modality also spread into pop music, with some chord progressions specific to modal scales becoming rooted in the entire genres.

The Mixolydian scale has only one alteration compared to the major scale which explains its major sound. But this change is quite significant since it robs the Mixolydian mode of the leading-tone, so the seventh scale degree—called the subtonic—differs from the tonic by a whole tone. This means that the dominant chord is a minor one and its use is minimized, depriving the Mixolydian mode of the very important perfect authentic cadence.

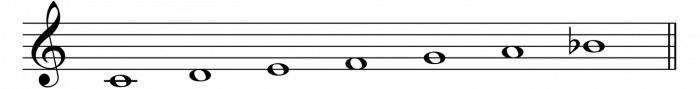

C Mixolydian scale:

The dominant function in the Mixolidyan mode is most often represented by the major subtonic chord, but cadences implemented with it are imperfect. Another option to be used in the final part of a composition is the plagal cadence, also known as the Amen cadence, a name brought by the hymn tradition and the frequent usage of the word amen in the closing part of the verse.

The dominant function in the Mixolidyan mode is most often represented by the major subtonic chord, but cadences implemented with it are imperfect. Another option to be used in the final part of a composition is the plagal cadence, also known as the Amen cadence, a name brought by the hymn tradition and the frequent usage of the word amen in the closing part of the verse.

During the Renaissance era, tonal theories were in their infancy, so the modal modes became widespread, as demonstrated by Canticum Canticorum—a famous series of motets published by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina in 1584. In this collection, vocal compositions are written using five different diatonic scales, including eight songs composed in G Mixolydian.

Listen to Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina's Surgam et circuibo civitatem performed by The Sixteen:

A rare example of the Mixolydian mode in Baroque music can be heard in the German Organ Mass, a collection of organ compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach published in 1739. This Bach's most significant and extensive work for organ contains 23 compositions, including a chorale prelude and a fugettha on the Lutheran hymn These are the holy Ten Commandments, both written in G Mixolydian.

Listen to Bach's Fughetta super: Dies sind die heilgen zehn Gebot performed by Alessio Corti:

Modality received a new impetus of popularity towards the end of the Romantic period when European composers like Edvard Grieg and Claude Debussy turned to folk music in search of national identity and developed new musical forms that could reflect evolving trends which would permeate both art and life of the early 20th century.

In 1925, the Italian post-romantic composer Ottorino Respighi wrote a piano concerto in E♭ Mixolydian trying to express the medieval genre of the Gregorian chant in modern orchestral form.

Listen to Ottorino Respighi's Concerto in modo misolidio - Moderato performed by Saxon State Theatre Orchestra:

Popular music is replete with songs that are either written entirely in the Mixolydian mode or simply contain a characteristic alternation of major chords between tonic and subtonic.

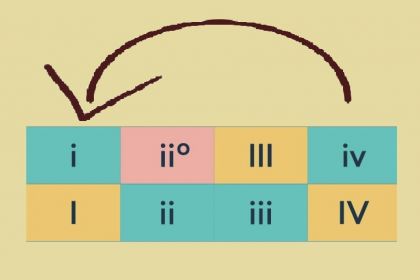

A curious example of a developed chord progression in the Mixolydian mode (as well as its connection to major scale) appears in If I Needed Someone by The Beatles. The harmonic analysis of the song's chord chain denotes scale degrees with Roman numerals, showing the following progressions:

- A–G–A or I–VII–I for the verses

- Em–F♯–Bm–Em–F♯–Bm–E or v–VI–ii–v–VI–ii–V for the chorus

In the verses, the chords follow a typical Mixolydian alternation, while the chorus starts with a minor dominant, then cleverly follows up with a powerful classical cadence using a major dominant chord. The Em chord changes to E chord through alteration of the seventh scale degree and then switches the Mixolydian diatonic scale to the major scale. In the chorus, the F♯ chord is marked in red since it does not belong to the Mixolydian mode where the chord built on the sixth scale degree should be minor and not major.

Listen to If I Needed Someone by The Beatles:

Seven Bridges Road, the famous 1980s song, written by Steve Young and then arranged by Iain Matthews, reveals another Mixolydian chord progression: D-C-G-D or I–VII–IV–I. Here, the same chord chain is repeated throughout the song, corresponding to the following sequence of the harmonic functions: T–D–S–T or tonic–dominant–subdominant–tonic.

Listen to Seven Bridges Road performed by Eagles:

L.A. Woman, the title track of the 1970 album The Doors, is based on the alternation of two major chords that are built on the first and seventh scales degrees of the Mixolydian mode: A–G–A or I–VII–I.

Listen to L.A. Woman by The Doors:

Mixolydian scale is not confined to the Western music canon—many world cultures have been known to use it since antiquity. Its counterpart in Indian classical music is called Khamaj thaat which is suitable for performing such ragas as Rageshree, Jhinjhoti, and Desh.

Listen to Ravi Shankar perform Raga Rageshri featuring a pentatonic version of the Mixolydian scale:

Close analogs of the Mixolydian scale are also described by Turkish makam and Arabic maqam which are the main melodic systems of the Middle East.

I’m so glad to see a comprehensive article on the history of the Mixolydian scale, well done. I might just add ( although you can’t list them all ) that there are actually a number tunes from the 1960s on up that get over looked as Mixolydian songs. Also I agree the folk aspect is strong, not the least from the British isles that first hit North America a few centuries back. In the 1960s with the folk revival and British Invasion this recharged its presence. One last thing if I may, the fusion of major and minor pentatonic in one tune sort of arrives there as well.

Thanks for the article and the opportunity to comment.

JP

Thank you for your input! I just finished another article on the subject when I saw your comment. This one features harmonic analyses of a few more songs from the 1960s and 1970s. I have to admit when analyzing the songs, I generally focus on chord progressions and do not pay attention to the melody, so I am intrigued by your idea of combining two pentatonic scales in one melody, sounds fascinating. Though I don't think I fully grasp your meaning, could you please explain it in more detail?

Hello,

Thank you I enjoy your articles and the opportunity for such a great conversation and topic.

If we generalize for a moment, We can look at two real expressive / lyrical folk scales, minor and major pentatonic. All though not exclusive the major is usually thought of as a country / folk scale with Scots Irish roots etc. The minor is often associated with a blues scale from west Africa. As we get into the rock era we begin to hear a more distinct combo of the two scales in one solo. Earlier on its presented as a occasional m3 or m7 in a major key, talking about swing, early R&R etc. I also think as more guitar method books started to become available these patterns were presented as two applications.

Mixolydian - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7b 8

Major Penta - 1 2 3 5 6 8

minor Penta - 1 3b 4 5 7b 8 (3b)*

Incidentally, it isn’t that uncommon in traditional Appalachia, British etc folk to have a shift between Mixolydian & Dorian in one tune.

Your right about progressions, sometimes the chords and vocal melody are Mixolydian and the solo is Minor Pentatonic.

I really like the following rock tunes for Mixolydian examples.

Journey to the Center of the Mind ( The Amboy Dukes )

Shapes of Things ( The Yardbirds )

I think Rebel Rebel ( David Bowie )might be one.

Thank you Sir, I hope I wasn’t to long winded.

Josh🎸

Hi, Josh! Thank you for such a detailed explanation.

Indeed, the necessity to perform the minor pentatonic melody in the Mixolydian mode is a good rationale for using a major chord built in the third scale degree ♭III as shown in Clocks by Coldplay and Sweet Home Alabama by Lynyrd Skynyrd mentioned in this article.

I listened with pleasure to the songs you mentioned and found them very interesting. The first two contain explicit Mixolydian sections while David Bowie's Rebel Rebel adheres entirely to Mixolydian harmony.

I hope we could continue engaging on similar topics in-depth even more in the future!

Hi Serg,

Thank you for having a listen to my previously mention tunes, also for the analysis. I also want to thank you for pointing out the bIII function against the mixolydian I chord. That I can recall, I don’t believe I’ve thought of the minor pentatonic relationship that way beyond the b3 blue note aspect against a major chord. Of course it’s right there and makes sense. I love when your shifted a bit to see something from a certain angle! But again that is brilliant because we know rock will not just use p5s a m3 apart, but also full major chords. Hey by the way, No Rain by Blind Mellon is a pretty cool mixolydian jam. It does occasionally land on the A Major , but I get a heavy vibe of the E mixolydian in that one.

Cheers

Josh.

P.S. I just got done chilling out to Marquee Moon, been a while, what a jam.

Hi, Josh!

Indeed, the last example given by you is written entirely in E Mixolydian with the exception of ♭III which I marked in red.

No Rain by Blind Melon:

Since we have discussed three more songs here, I want to give their harmonic analysis and a little bit of commentary.

Rebel Rebel by David Bowie fully adheres to E Mixolydian:

Shapes Of Things by The Yardbirds:

In the choruses, we see some chords that do not correspond to G Mixolydian. It's once again the ♭III major chord built on a lowered third degree and the V major dominant chord instead of a minor chord built on a fifth degree.

Journey To The Center Of The Mind by The Amboy Dukes:

There is a discrepancy to E Mixolydian in the third verse: the supertonic chord should be minor and not major. It seems that the progression used in the choruses cannot be explained by any of the diatonic scales. This stepwise downward movement of major chords (rooted in chromatic scale degrees) sounds very tense to me and leads to nowhere, although it ends on the A subdominant chord. I have already encountered a similar sequence in The Doors' Wishful Sinful, where I feel it poses greater difficulty for Morrison to sing against the background of such an unusual harmony.

p.s. Power chords are often used in music accompaniment, however, the adherence of vocal, bass, and other lines to minor or major modes is typically shown in the third.

Hi Serg!

Man you are really on top of things! Great analysis on all of the above additions. Shapes of Things is really fun the way the IV & bIII mirrors the I & bVII. I also like the guitar solo. One can almost imagine pipes or a fiddle in mixolydian against a marching snare!

With the F# in Journey to the Center of the Mind, could we think of it as a triple dominant against an A Ionian only with a straight major?Perhaps acting like a double dominant, 5 of the 5 kind of thing as if in E Ionian for that section. You know like a lot of old time folk tunes in C for example, that have that D7 to G7. Although I know straight majors in that role can be a bit clunky with out the minor seven leading. Maybe I’m over thinking it. I’ll often with my own stuff kind of bash it out and then analyze it as I develop it further.

I seem to recall Pete Townsend of The Who mentioning, When using power chords the over tones and other instruments will provide the thirds. I agree, creates space and nice arrangements in rock.

Cheers

Josh

Hi Josh!

Oh, I have never come across the term "triple dominant" and a google search does not shed light on this question, so could you please clarify it a little, if possible?

Of course, we can consider F♯ as a secondary chord to the Ionian or Mixolydian dominant. In this case, the B Ionian dominant or the Bm Mixolydian dominant should appear immediately after F♯. Since the progression E–C♯m–A–F♯–E does not contain a dominant chord at all, there can also be no double dominant here. I tend to think that the songwriter just wanted to write a major supertonic chord instead of a minor one. It is not uncommon in classical music to use major supertonic chords in the Ionian major but it's usually realized by lowering the second scale degree in which the Neapolitan chord is rooted.

Hi Serg,

Great follow up and good to know that a major supersonic is not uncommon in classical. I’m sure at some point I’ve been struck by that while listening to classical, just didn’t realize it was common. Funny thing, I noticed there wasn’t any information on triple dominants as well with google.

It has been a reasonably common term, around my shop, with band mates and friends. It was also presented to me years back by a teacher of mine as simply using dominants. Ok I am almost certain that this is familiar to you from a different angle, which I would love to hear your description.

Using dominants

CMaj Dmin Emin FMaj GMaj Amin Bdim

D7 E7 A7 B7

CMa7 G7

I V

V of V = D7 ( double dominant )

V = A7 ( triple dominant )

V = E7 ( quad dominant )

V = B7 ( quin dominant )

Guiding tones leading into each other while moving in 4ths, like in the bridge of I’ve Got Rhythm.

D7 G7 C7 F7 in Bb.

III7 VI7 II7 V7

I have to admit that I rarely hear the term used after triple, which doesn’t really help the legitimacy of the terms. However for years we have used these titles in reference to pop, rock and jazz, at least in California where I’m located. I also know that Bach played a big part in all this. Like I mentioned above, I’m interested in your description.

Thank you

Josh

Hi Josh,

Thanks, the concept of the triple dominant is clearer now. In theory, this refers to tonicization, that is, the temporary establishment of another tonic chord. Unlike modulation, tonicization usually lasts no longer than one or two bars.

Tonicization applies to any scale degree of any key except those scale degrees that support the diminished chord. So, in C major key, the tonicization of the second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth scale degrees is generally accepted. In other words, the chords Dm, Em, F, G, and Am can temporarily act as a tonic chord. This is considered to be a very powerful compositional technique often used to refresh a recurring musical section.

So-called secondary chords are used to establish a new tonic chord. In the simplest case, the new key is established by the authentic V–I cadence where I is the new tonic chord of the new key and V is the secondary chord—the fifth-degree dominant chord that introduces the said key. For example, the simplest tonicization of the fifth degree in C major key is D-G, and here the secondary D chord can be called a double dominant. However, tonicization can involve other chords as well as combinations of them including a fourth-degree subdominant chord of a new key: C-D-G. Here, C is the secondary subdominant chord, D is the secondary dominant chord, and G is the new tonic.

Here are all the secondary dominant chords that can apply the tonicization in C major:

A for Dm

B for Em

C for F

D for G

E for Am

The most important thing here is that secondary chords do not make sense on their own and they sound extremely alien when appearing in progressions if they don't also establish a new tonic chord. Moreover, it is not advisable to use secondary chords in the first beat of a measure, since they generally do not belong to the original key and sound quite harsh.

As for the terminology, only the term double dominant makes sense. For example, in the case of tonicization of the second degree in the C major key by the sequence A–Dm, the A chord is the secondary dominant chord for the tonic Dm chord. Here, A chord cannot be called a double dominant, because it's a secondary dominant chord that establishes the new tonic chord in only the second degree and not the fifth degree.

I am thinking about writing an advanced article about tonicization if you find that this presentation of mine is understandable and does not seem too complicated.

Hi Serg,

This is much appreciated and I encourage you to write an article on the subject. It makes sense to me. I have heard the term tonicization here and there and although the term it self is evident I never really have seen it applied descriptively, that remember anyway. I hear and have thought about examples like the following.

Key C major and then a section arrives with Em to B7, a harmonic minor idea off the iii instead of vi. Kind of a dreamy feel. There are also those tunes from musicals and or trad jazz that seem to loop as such

A7 D7 G7 C C7 B7 Bb7 repeat. Is this what you mean about harsh? I know even though I like it at times, when you solo to it and extend to far ones ear can begin to jump and look for a landing pad (tonic). However examples like this do eventually land on a tonic ( C like above ). The other thing is, tunes like this generally had an intro that was dropped later by jazz artist. People began to add a ii that preceded the v to smooth things out some. I’m not insinuating that the ii v progression didn’t exist before say the 1940s, just that there seemed to be a desire to bring it in on new tunes and older ones. I like both styles depending on my mood or sub genre. I know what you mean about harsh though, assuming my example is in line with yours.

Thank you

Josh

Hi Josh,

Suddenly appearing chords that do not belong to the key of the piece can sound rather harsh when viewed from the tonal theory standpoint that was formed several centuries ago but is still the basis of musical education today. In the early 20th century, many of the rules in classical music were rejected and rewritten. The new compositional techniques of modernism and serialism had little to do with the tonal theory while the Second Venetian School theorized atonal music. Since its inception, popular music also did not particularly strive for classicalism, and these days many songwriters often manage with just two chords.

My position is that all music makes sense but the knowledge of tonal theory does not interfere with creativity in any way since it fully fits with other sciences explaining physical processes in our world. Indeed, it is better to know the theory in order to look for new ways to refresh or break it than just try to compile harmony at random or imitating someone.

I'm afraid it will be difficult to find examples of tonicization in pop music but I can give some sequences to explain how it works. Here is a typical cadence sequence in C major: C–Am–F–G–C or I–vi–IV–V–I.

Now let's look at it when it's just one chord per measure: C.../Am.../F.../G.../C...

And here is how it can be enhanced by tonicizing the sixth and fourth degrees with the help of secondary dominants performed on the fourth beat: C..E/Am..C/F.../G.../C...

I think you will agree that this sounds very impressive. The progressions using secondary chords are usually denoted in the harmonic analysis as C–E→Am–C→F–G–C or I–V/vi→vi–V/IV→IV–V–I.

I will think about a clearer way to show the tonicization of each degree in future articles and I also hope to find at least a couple of song examples.

You are right about jazz, its tunes are often based on the circle of fifths, and thus they create long sequences of secondary dominants.

Hi Serg,

Makes good sense, thanks for the reply.

Josh