Classical Guitar

Giulio Regondi, the guitar prodigy behind early Romantic repertoire, was conned by false parent

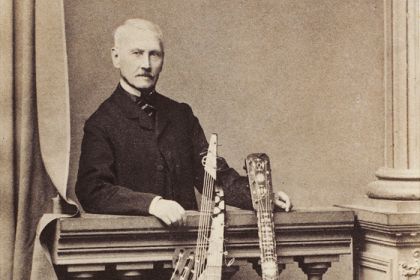

Giulio Regondi

Giulio Regondi was one of the most virtuosic guitarists of the early Romantic period who began earning flattering reviews from eight years of age including the praise of the violin maestro Paganini. Europe admired Regondi's exceptional technique while his emotional compositions were compared in complexity to the piano works of Franz Liszt and Charles-Valentin Alkan.

The fact that the greatest guitarist Fernando Sor has dedicated one of his pieces to a nine-year-old boy speaks of Regondi's unprecedented skill: after all, Regondi was only a child when he mastered the guitar, a rather complex instrument that required about 20 years of intensive training to form real virtuosity.

Born in 1823 in Geneva (other sources say Lyon), Regondi was raised by a man who proclaimed himself to be his father after his mother died during childbirth. Having discovered the musical talent of the boy at a very early age, the self-proclaimed father set out to raise a young prodigy who would provide him with a stable income.

The training methods were very harsh, too, with the boy being locked in a room where there was only a guitar, a collection of etudes and a stern neighbor who made sure that the child’s exercises were not interrupted.

Giulio Regondi at the Royal Adelphi Theatre in London in 1831:

With such intensive practice, Regondi's skill very soon made him a guitar genius that, combined with his angelic appearance and maturely developed intellect, allowed him to conquer the European stage by throwing music critics into absolute ecstasy.

In one of the many reviews accompanying Regondi's first London tour, The Harmonicon expressed some concern about the early development of the boy's artistic gift:

"To say that he plays with accuracy and neatness is only doing him scanty justice; to correctness in both time and tune he adds a power of expression and a depth of feeling which would be admired in an adult, in him they show a precocity at once amazing and alarming; for how commonly are such geniuses either cut off by the preternatural action of the mind, or mentally exhausted at an age when the intellects of ordinary persons are beginning to arrive at their full strength!"

The same article described the appearance of the musician and the magic of his personal charm:

"The personal appearance of the almost infant Giulio at once excites a strong feeling in his favour. A well-proportioned, remarkably fair child, with an animated countenance, whose long flaxen locks curl gracefully over his neck and shoulders, and whose every attitude and action seem elegant by nature, not art, immediately interests the beholder; but when he touches the string and draws forth from it tones that for beauty have hardly ever been exceeded; when his eye shows what his heart feels, it is then that our admiration is at the highest, and we confess the power of the youthful genius. This child is the most pleasing prodigy that our time has produced."

For several years, the child prodigy had earned with his recitals a fortune estimated 2000 pounds with which his pseudo-father disappeared, leaving a twelve-year-old musician only five pounds. The emotional and financial crisis caused by this cynical betrayal was overcome by Regondi with the help of two people: a poetess named Madame Fauche and the father of the pianist Richard Hoffman who actually gave him parental support.

Shortly before her death, the poetess even published her tribute to Regondi:

Blessing and love be round thee, fair boy!

Never may suffering wake a deeper tone,

Than genius now, in its first fearless joy

calls forth exulting from the chords which own

Thy fairy touch! Oh! mayst thou ne’er be taught

the power whose fountain is in troubled thought!

For in the light of those confiding eyes

and on the ingenuous calm of that clear brow,

A dower, more precious e’en than genius lies,

A pure mind’s worth, a warm heart’s vernal glow!

In the following years, Regondi settled in London, reinforcing his fame as a performer and composer with intensive tours in Europe, filling his repertoire with guitar interpretations of the most complex works such as Rossini’s Overture to Semiramide.

Years later, Regondi forgave his pseudo-father and, in response to a letter of help due to poor health, provided him with housing in London and maintenance.

Listen to Giulio Regondi's Fête Villageoise performed by Leif Christensen:

By the mid-19th century, the general trend of the Romantic era pushed the piano to the forefront of popular art, putting the guitar into oblivion for several generations. The situation forced Regondi to shift his attention to the newly invented concertina—an accordion-like instrument for which the composer wrote a significant amount of work and achieved performing mastery, but this did not return his former fame and income.

The last years of Regondi’s life were also overshadowed by the terrible suffering from cancer. His American friend Richard Hoffman wrote in his Recollections:

"His lovely spirit passed away after many months of suffering from that most cruel of all diseases, cancer. I remember that a certain hope of reprieve from the dread sentence was instilled by his physicians and friends, by telling him that, if only he could obtain some of the American condurango plant, which at that time was supposed to be a cure for this malady he might at least be relieved. I sent him a quantity of the preparation, but it failed to help him, and so he died, alone in London lodgings, but not uncared for, nor yet unwept, unhonoured, or unsung."

Giulio Regondi died on Monday, 6 May 1872, at a small house near Hyde Park in London. His creative legacy has sunk into oblivion and was rediscovered by modern guitarists only a hundred years later.

Great article. Sounds like a story Dickens could have written.

There should be more research on him. I don't know if I believe the man who raised him was an impostor or "false parent".

And also, I'm not sure that he abandoned the guitar in his later years as many seem to think. Various editions of "The Musical World" indicate that we was performing on the guitar throughout the 1860's. For example, Volume 42 of that publication reveals that 1864 was the year that he premiered Introduction et Caprice.

All though, he seemed to perform more on the concertina towards the end of his career. That's what the concert reviews suggest. Or it could be that the guitar declined in popularity to the point that the audience wouldn't make note of it.

Not so true Julian Arcas at this period made a great career, in 1862 he played in London for the royal family.

In fact the guitar is also transitioning to the modern style guitar.

It is not a break, and Regondi is the first guitarist I think to develop a tremolo technique. (unless mistaking)

But maybe he had the problem of prodigy children when they get adult , if they are not well communicating, everybody think that they already gave all what they have.

I have read about a “decline of the guitar” around the time period. But maybe it is just the prodigy phenomenon in which he’s really famous as a kid but like you say doesn’t keep it up in adult years. That might be the most reasonable explanation.

I’ve done research on tremolo and it was definitely hard to find examples of a full-fledged tremolo written earlier than Regondi’s Don Giovanni variations (I believe he performed that in 1839.) It definitely makes me curious about how he learned tremolo.

maybe the idea was in the air at this time after Liszt 2nd rhapsody

that’s an interesting hypothesis and worth an investigation!

There are earlier tremolo pieces. Mertz used it a lot. But really early (1810 or something) Salvador Castro de Gistau used it in his Fandango.

I've tried to find some early Mertz examples. He did use it in his Ernani fantasie from Op. 8, but that might've been later than Regondi's Don Giovanni. I will have to look up this Salvador Castro de Gistau!

Sad to have been raised that way and taken advantage of but his pure heart was forgiving. He left behind a wonderful gift.