Veena

Sundaram Balachander: the veena musician and filmmaker who introduced Carnatic culture to the world

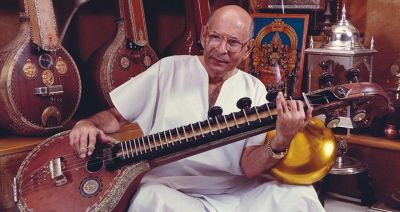

Sundaram Balachander

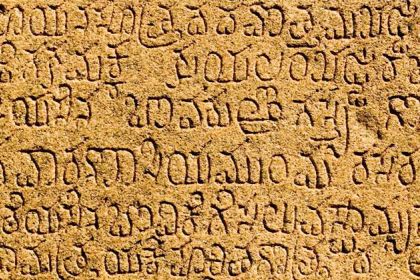

The veena is the oldest string instrument of the Indian subcontinent, first mentioned in the Rigveda dating back to 1500 BCE. At first, the veena came in many designs due to differences of regional modifications, the number of which was eventually reduced to about a dozen. All 12 of its remaining current designs influenced the appearance of almost all string instruments involved in Indian classical music such as sitar, sarod, and sarangi.

In the past few centuries, when Indian classical music had its most profound development, the veena was overshadowed by more accessible instruments yet it retained its significant role in Carnatic tradition in the South. This historically important instrument has regained its former popularity thanks to Sundaram Balachander whose astonishing playing technique allowed the most exquisite ragas to be performed on the veena.

Sundaram Balachander was born in 1927 in Madras, where from his early childhood he showed many talents by participating in chess tournaments, musical performances and playing in films. His first role came to him when he was six: the part of a child musician in Ravana's court in a Tamil film by famous director V. Shantaram who noticed the boy's inclination to make music and presented him with a set of tabla drums.

Balachander is considered to be an outstanding musician firstly due to his having mastered many instruments on his own without having a permanent guru and not adhering to the traditions of any particular gharana. Secondly, apart from his dazzling musical abilities, Sundaram Balachander developed a steady career in cinema as a director, screenwriter, and composer.

S. Balachander at 1950:

By the age of nine, Sundaram Balachander had already demonstrated good skills by playing in temple musical events on a majority of Indian rhythmic instruments such as the tabla and kanjeera, so he made a decision to switch to the melodic patterns of Indian classics and initiated self-education on the sitar. However, he soon realized that the sitar—intended for rather high-speed passages—did not provide enough sustain to express the musical nuances of the Carnatic tradition for which he had had a passion since childhood.

Roughly from the beginning of his All India Radio employment at the age of fifteen, he chose the Saraswati veena as his main instrument, named so after the Hindu goddess Saraswati who was usually depicted with a veena. It is reported that in just a few years he developed an extraordinary skill, presenting a new trend, new style, and new school of veena-playing.

Goddess Saraswati by Raja Ravi Varma:

Sundaram Balachander's extraordinary mastery on the veena as well as his acquaintance with such popularizers of Indian classical music in the West as sitarist Ravi Shankar and violinist Yehudi Menuhin laid the foundation for this old instrument to achieve the level of international recognition. At the same time, Balachander always avoided any kind of fusion or cross-genre collaborations in the belief that while it could be a good way to make a well-selling record, it could also endanger the integrity of the spiritual essence held in Indian musical traditions.

Being a constant improviser, Sundaram Balachander never knew for certain which ragas he would play in the upcoming concert, leaving this choice to the intuitive impulse that came from the connection between the performer and the listeners.

He died in 1990 of a massive heart attack during his concert tour of the country.

Listen to Sundaram Balachander play Amritavarshini ragam:

Even though there is a belief that the 18th-century Indian composer Muthuswami Dikshitar caused rain by performing Amr̥tavarṣiṇi raga, its sound is still associated with joy, exuberance, appeal, and passionate exultation.

From the perspective of Western musical theory, Amr̥tavarṣiṇi raga is based on a symmetrical pentatonic scale containing three notes of the tonic triad and lower leading-notes to the tonic and to the fifth. It shows the absence of subdominant harmony in the scale which gives Amr̥tavarṣiṇi raag its authentic decisive character.

Since the leading-tone to the fifth is the hallmark of the blues genre, Amritavarshini raga can be slightly associated with the blues slide guitar techniques.