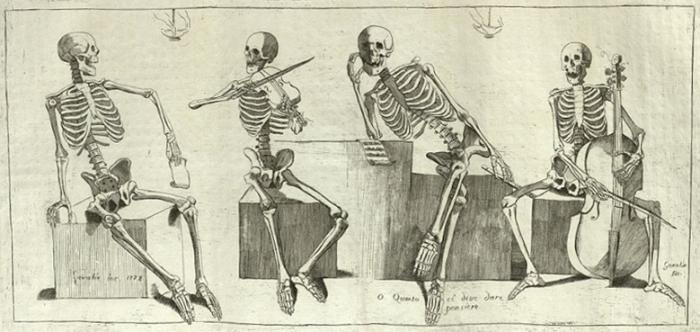

Cello

Recent study of Luigi Boccherini's skeleton revealed the threat of scoliosis for cellists

Statue Of Luigi Boccherini in Lucca by Daphné Du Barry

Luigi Boccherini was born in the Italian town of Lucca in Tuscany in 1743. He was the third child of a double-bass player, Leopoldo Boccherini, and the brother of Giovanni Boccherini, a notable poet and dancer who wrote librettos for Antonio Salieri and Joseph Haydn.

The Boccherini patriarch started giving Luigi cello lessons when the boy was five years old, though later on, from the age of nine, Luigi continued his studies with Abbé Vanucci, music director of the cathedral at San Martino.

When Luigi reached the age of thirteen, he was sent to Rome to study with the renowned cellist Giovanni Battista Costanzi, the then musical director at Saint Peter’s Basilica. It was there that Boccherini was influenced by the polyphonic tradition stemming from the choral works of Giovanni da Palestrina and instrumental music of Arcangelo Corelli.

In 1765, Boccherini and his father went to Milan which at the time attracted all sorts of talented musicians as it was a place for them to thrive. Next year when his father died, the composer formed a new partnership with the violinist Filippo Manfredi. They toured Italy for one year and made their way to Paris, where they became a sensation.

It was the Spanish ambassador to Paris who in 1769 persuaded Boccherini to move to Madrid, where he began his long sojourn at the intrigue-ridden court of Charles III. He stayed in Spain for the remainder of his life.

Among Boccherini's patrons was the French consul Lucien Bonaparte, as well as King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, himself an amateur cellist, flautist, and overall an avid supporter of the arts.

In 1798, the new king of Prussia refused to extend Boccherini’s pension. Next year the composer entered into an arrangement with the publisher and piano manufacturer Ignaz Pleyel, who both praised and distributed Boccherini's works.

Listen to the first movement of Boccherini's Cello Concerto in B Flat performed by Jacqueline du Pré with the English Chamber Orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim:

In 1803, Boccherini was reported as living in "distress," but this is as likely from emotional depression as financial hardship, for in 1802 two of his daughters died from an epidemic within a few days of each other. In 1804, both his wife and his only living daughter followed. It seems clear now that Boccherini, although he continued to compose up to the end, had little interest in living, and died in 1805, of what was described as "pulmonary suffocation."

He was buried in the Church of San Justo in Madrid. In 1927 his remains were disinterred and he was reburied in the Basilica of San Francesco in his hometown of Lucca.

Not many of Luigi Boccherini`s compositions are performed today, but his name is very important in the history of music, for he, along with Haydn, definitely established the form of string-quartet, for which he wrote a hundred works, with every composition retaining melodic invention and charm.

Musicologist François Joseph Fétis wrote:

"Rarely has a composer had the merit of originality, to a greater degree than Boccherini. His ideas are always original, and his works are so remarkable... His harmony is rich in effects... His adagios and his minuets are always delicious... With a merit so remarkable, it is strange that Boccherini should not be better known today..."

Recent paleopathological study of Luigi Boccherini unveiled an accurate image of typical ailments suffered by Classical era cellists which was based on the lesions diagnosed on his skeleton.

The bow, held in the right hand, is strenuously pushed and pulled on the fingerboard, leading to stretching and flexion of the right thumb. Boccherini spent his life playing the cello and therefore his thumb joint was subjected to this repeated movement which evolved into rhizoarthritis of the right thumb.

The left hand holds the neck of the cello and, simultaneously, the fingers are moved on the fingerboard; during these actions the elbow, arm, and shoulder are constantly moved, causing severe left epicondylitis—a condition now commonly referred to as "tennis elbow".

The Classical era cello is smaller than the modern cello, without the spike. The absence of this endpin means the musician must hold the instrument between their thighs, knees and legs, causing the deformity of the shinbone.

After the cello got its modern spike which raised the instrument's height, it has reduced the possibility of joint deformity and scoliosis, but the cello player is still forced to maintain an unnatural position, meaning that most modern players share the same health risks as their forerunners.